Describes two methods for proportioning and modifying structural grade concrete proportions containing lightweight aggregates with examples. The method of weight (pycnometer) uses a common gravity factor calculated on the aggregates by a displacement pycnometer test (Method 1). The weight equation also uses the specific gravity function to measure the fresh concrete’s weight per yd. The system of wet, loose density uses the relationship between cement content and strength to model both lightweight concrete and sand lightweight (System 2). ACI 211.2-98 ACI Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Structural Lightweight Concrete.

Examples are given for systematic batch weight measurement, active displacement volumes, and adjustment to account for changes in aggregate moisture content, aggregate proportions, cement content, slump and/or air content.

ACI 211.2-98 ACI Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Structural Lightweight Concrete

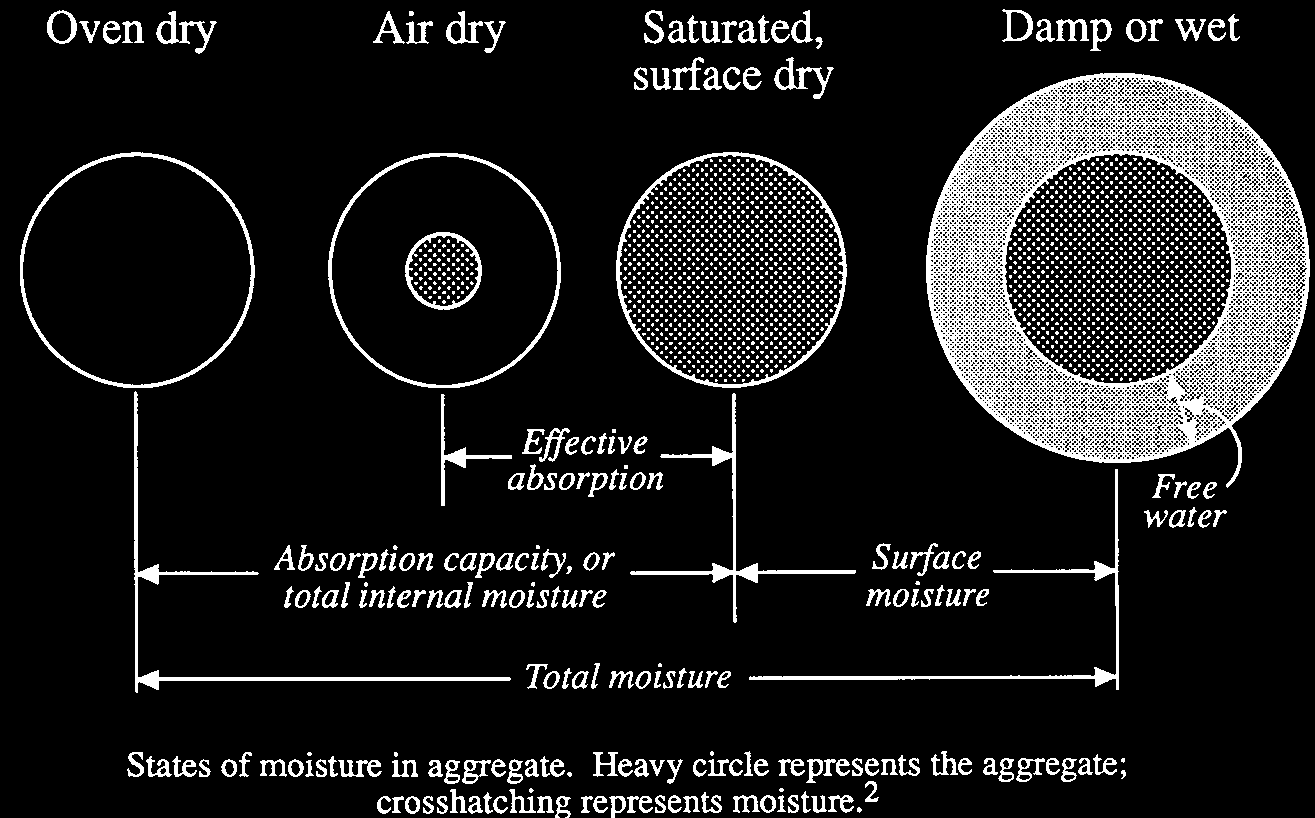

ACI 211.2-98 ACI Standard Practice for Selecting Proportions for Structural Lightweight ConcreteIn order to be practical for most concrete proportions of the mixture, aggregate proportions should be listed in a readily attainable moisture condition in the laboratory and in the field. The main problem in structural lightweight concrete is to properly account for the moisture in, (absorbed) and on, (adsorbed), the lightweight aggregate particles as well as the absorption effects for a particular application. Concrete technologists have traditionally assumed that aggregates are in one of the four conditions at the time of use for aggregate moisture content correction purposes. Such four conditions are shown in Fig. (a).

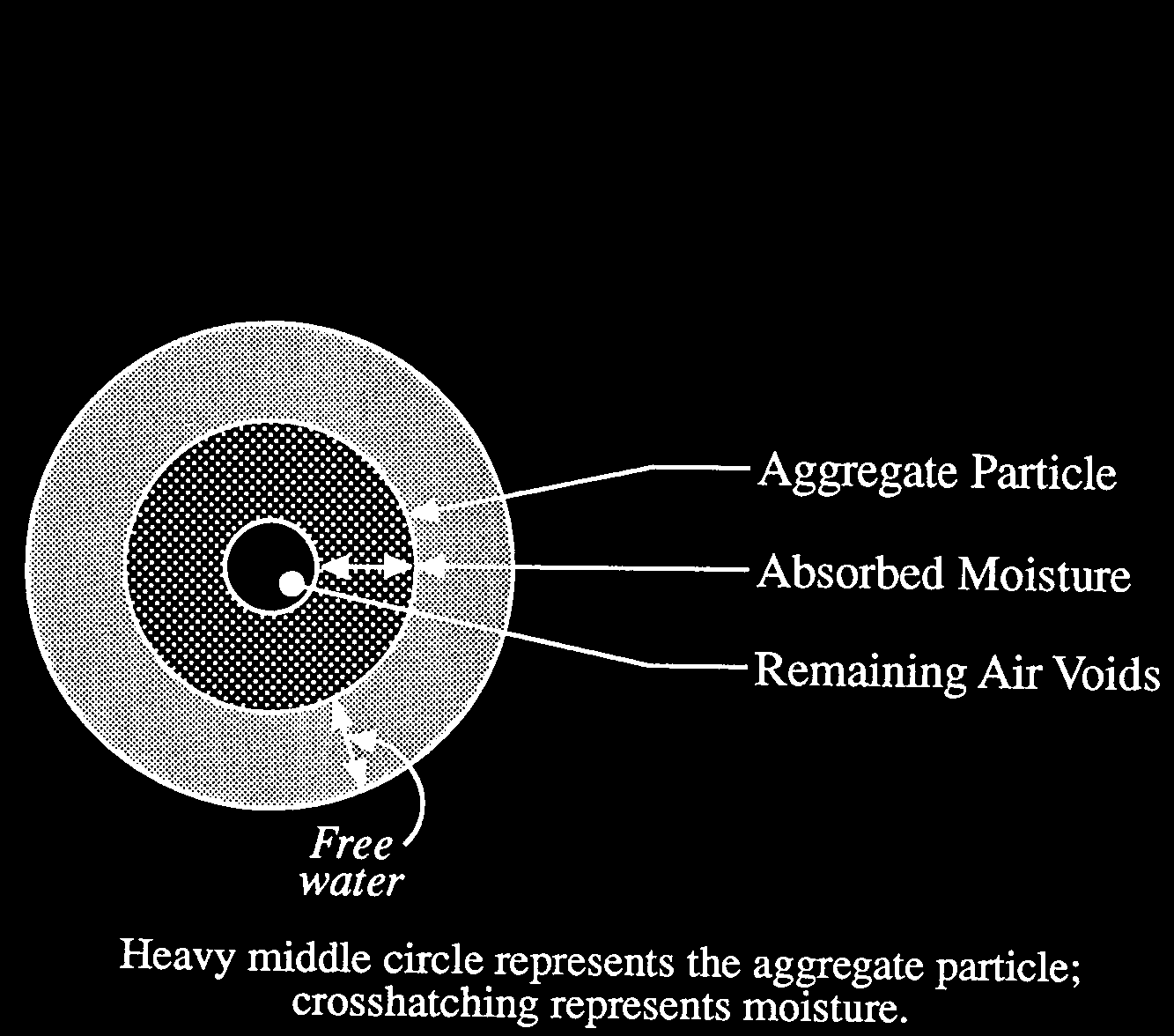

In either saturated, surface-dry (SSD) or oven-dry (OD) condition, most concrete mixture proportions are reported with agregates. But the aggregates in the field are typically air-dry (AD) or wet. Nonetheless, typically a unique situation provides a lightweight composite. In the oven-dry state, the majority of structural lightweight aggregate concrete mixture proportions are recorded. They’re not SSD in the field, however, but in a humid or wet condition. Sprinkling, boiling, thermal quenching, and vacuum saturation usually achieve this state. Occasionally, the outcome is called the “as-is” state (b).

The main problem for the concrete technologist is to have an easy method to use field data to translate the proportions of the oven-dry laboratory sample to the proportions in the moisture state “as-is.”