Acidic corrosion, also known as acid corrosion, refers to the degradation of materials caused by exposure to acidic substances. It occurs when acidic compounds come into contact with metal surfaces, leading to chemical reactions that weaken and deteriorate the material over time. Acidic corrosion can occur in various environments, including industrial settings, marine environments, and areas with high levels of air pollution.

In corrosion of the ferrous alloys due to acidic environment the dominating chemical reaction is Fe + 2H+ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐→ Fe + H2 .

Acidic Corrosion and It’s Mechanism.

There are various known damage mechanisms associated with the acidic environments of different kinds. Some of the important mechanisms in this group are given below.

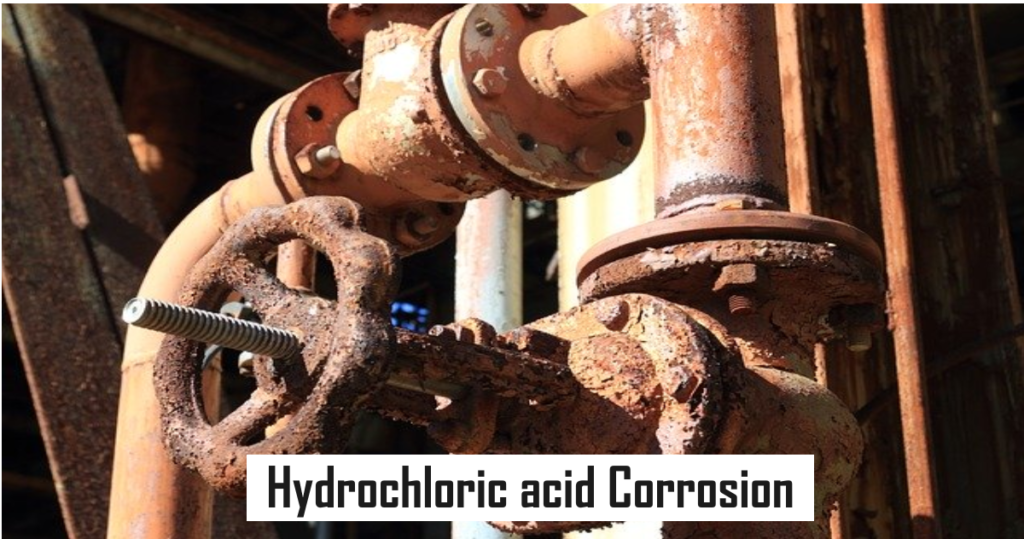

a) Hydrochloric acid Corrosion.

Dry Hydrogen Chloride is not corrosive, however in presence of moisture the aqueous hydrochloric acid is formed and very aggressive general and localized corrosion is caused by condensed vapors of aqueous HCl.

Most affected are the vessels and the piping made with carbon and low alloy steels. The severity of corrosion increases with increasing HCl concentration and temperature. The HCl corrosion is not the problem only in the process streams where direct HCl is used or generated, but also in the processes involving chloride salts like ammonium chloride or amine hydrochloride.

The deposits of these salts usually absorb the moisture in the process stream and transform into the aqueous hydrochloric acid which corrodes the metal in form of under deposited corrosion, as discussed earlier. Any equipment which can deposit these salts should be inspected by ultrasonic scanning or other on stream inspection techniques while being in service.

Most Vulnerable locations include systems containing the overheads from crude atmospheric distillation tower, especially the condensing equipment. Similarly in the systems containing the chloride salts like hydro processing, catalytic reforming and the amine stripping can also be affected by generation of HCL as the process byproduct. Unit Inspector and the corrosion engineer should closely observe lab results for the chloride contents and pH of the process streams.

The OSI and other inspection planning should be developed accordingly. The appropriate methods of detection are the profile radiography and ultrasonic scanning at the vulnerable location on the piping. And for the vessels the appropriate methods are the ultrasonic thickness measurement and thorough visual inspection at the shutdowns.

Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.4.

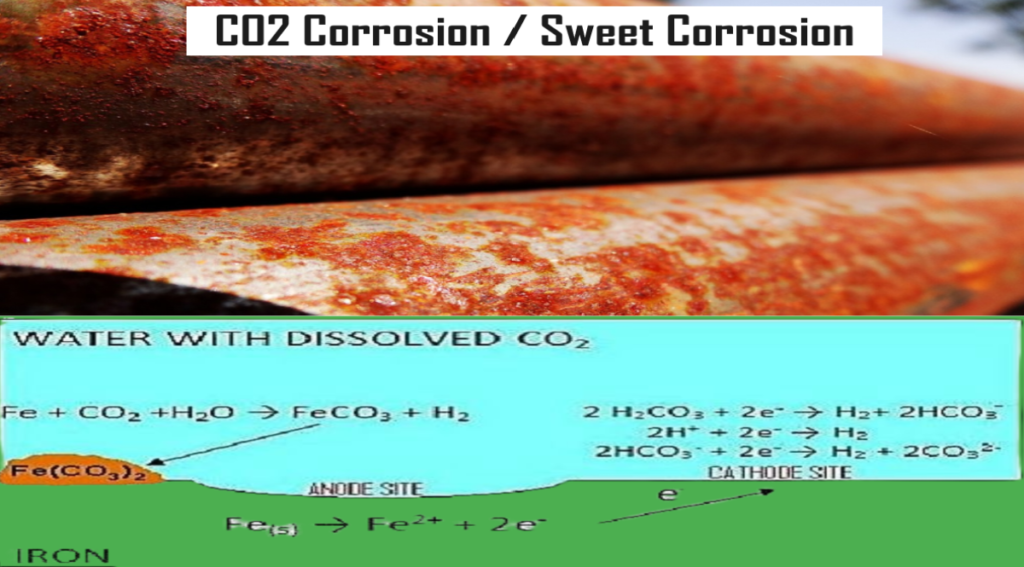

b) CO2 Corrosion/Sweet Corrosion.

When CO2 is dissolved into water it generates week carbonic acid (H2CO3) which causes severe localized and general corrosion in carbon and low alloy steels, often referred as sweet corrosion (if H2S component does not exists in the stream). The sweet corrosion mostly affects the carbon and low alloy steel, while the high alloy steel with higher chromium percentage, and stainless steels are relatively immune to the CO2 corrosion.

The governing factors for this corrosion are the concentration of condensed CO2, temperature, and stream flow velocities. That is why most vulnerable areas are the bottom of the vessels (near drain boot), and water drain lines. CO2 corrosion heavily affects the welds in the water drain lines, causing the preferential corrosion of the HAZ and the welds. The preferential weld corrosion is further discussed in Para 1.5 of this section.

The CO2 corrosion damage could be localized or generalized, depending on the flow condition of the corrosive water. It may appear as localized thining or deep pitting in case of stagnant condition, or as deep grooving in the areas of high flow velocities and turbulence. In case of the wider area with steady flow conditions (for example in tanks near the sump pit and the drain boot areas of large separators) the corrosion damage appears as mesas produced in rock by wind and water erosion. Due to this reason CO2 corrosion is also referred as Mesa Corrosion.

Visual testing, ultrasonic thickness measurement and the profile radiography are the best tools for the inspection of the CO2 corrosion. The inspector should pay special attention to the welds in drain lines handling the dissolved CO2. The experience has shown that welding quality in the drain lines is often not as good as in the process lines. Such lines often show accelerated washout on the welds due to corrosion induced by CO2. Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 4.3.6.

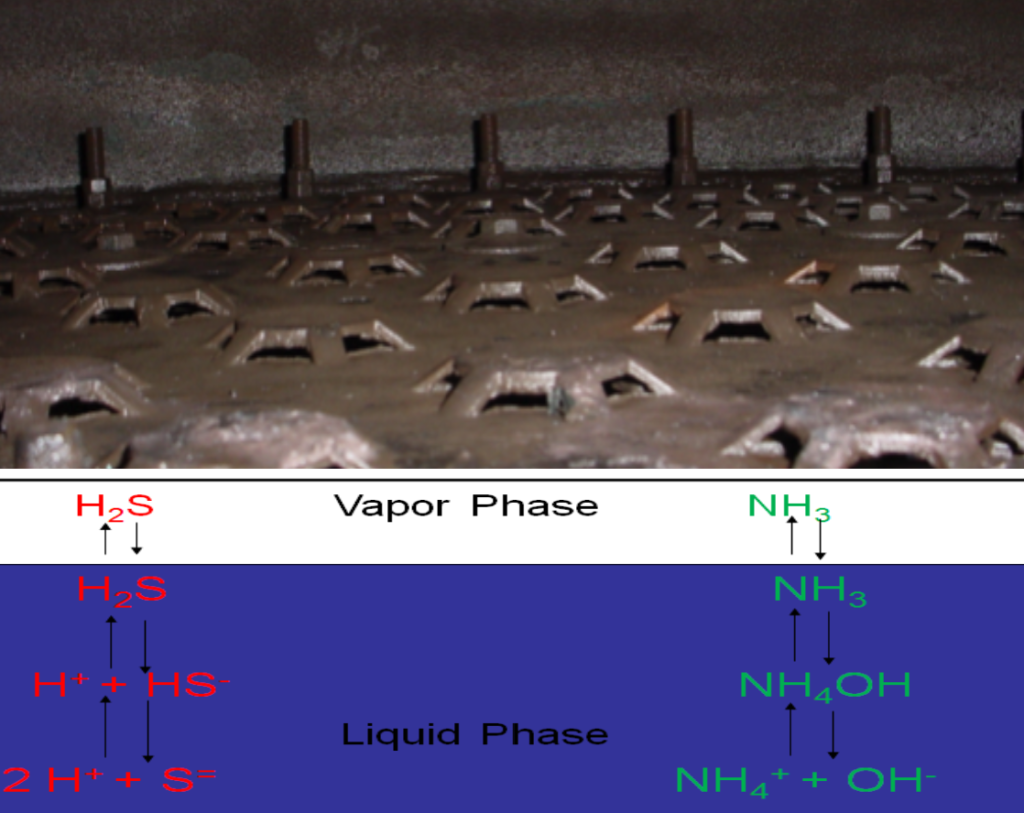

c) Sour Water Corrosion.

Sour water corrosion occurs when the process water streams have substantial amount of dissolve H2S. Usually the protective layer of blackish iron sulfide is formed on the internal surface of the piping and equipment handling the sour water.

Unless very high turbulent flow is not involved, the corrosion due to sour water is not as aggressive as sweet corrosion (due to CO2). Biggest concern in the sour system is the various hydrogen embrittlement damages.

The governing factors in the sour water corrosion are the concentration of H2S, and temperature of the stream. At lower concentration of H2S the pH of the water stays above 4.5. At this level of acidity the iron sulfide layer is relatively stable to protect the metal from corroding.

However corrosion tends to increase with the temperature and increasing concentration of the H2S, but the solubility of H2S in water also reduces as the temperature increases. It is worth noting that the pH of process streams is not controlled by H2S only, but other contaminants like HCl and CO2 also tend to reduce the pH of the stream. Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.10.

d) Sulfuric Acid Corrosion.

Some of the processes in chemical and refining industry use or generate the Sulfuric Acid as end product or byproduct, which causes both general and localized corrosion of carbon steel and other alloys. The major governing factors in the sulfuric acid corrosion are temperature, concentration, and flow velocity.

The reactivity however is different with different Alloys. Most vulnerable locations are the un-tempered welds (without PWHT) and the flow direction changed in the piping. Ultrasonic thickness measurement and profile radiography of the piping are the most effective on‐stream inspection methods.

Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.11.

e) Phosphoric Acid Corrosion.

Phosphoric acid is used as the catalyst in the polymerization units. Dry crystalline phosphoric acid is not very corrosive, however the corrosion becomes aggressive if water is mixed into the stream. As per API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.9.3.d the corrosion rate due to phosphoric acid with free water can be as high as 0.25” in 8 hours.

Hence the operation practices must be closely watched in the plants involving phosphoric acid as process ingredient. The major governing factors in the phosphoric acid corrosion are temperature, concentration, contamination of chloride ions, and flow velocity.

The reactivity however is different with different Alloys. Most of the corrosion due to phosphoric acid is believed to be occurring during water washing operations at shutdowns. Most vulnerable locations are the un‐tempered welds (without PWHT) and the flow direction changed in the piping. Ultrasonic thickness measurement and profile radiography of the piping are the most effective on‐stream inspection methods.

Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.9.

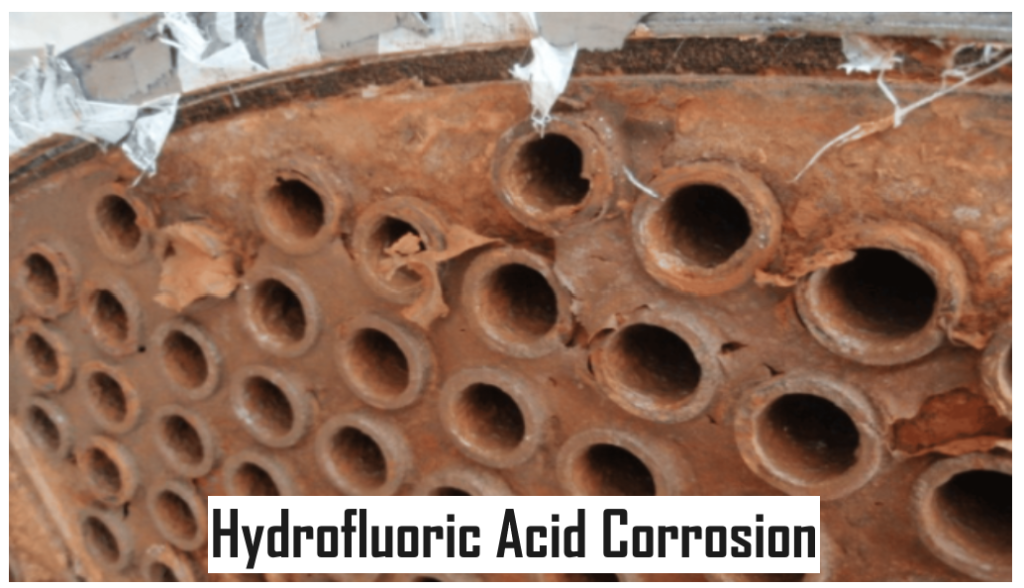

f) Hydrofluoric Acid Corrosion.

Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is used in alkylation units. Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is the strongest bonded acid in the halogen group of the acids, in other words its aqueous solution has lesser number of free H+ ions.

That is why concentrated hydrofluoric acid is not corrosive as compared to dilute acid with higher concentration of water. At higher concentration of HF (lesser water contents) the steel develops the protective fluoride layer. However in case of high flow velocities and turbulent flows this layers breaks apart and fresh layer is exposed for corrosion.

Normal alkylation units run at concentration of 97% to 99% and the temperatures are generally below 150oF (66oC), however if water contents and temperature increase the potential of corrosion increases. The HF acid corrosion can be localized or general and is often accompanied by hydrogen cracking, blistering and/or HIC/SOHIC, as discussed in Para 3.1.1 of this section.

Mostly the equipment and piping in the HF alkylation unit are affected by HF corrosion if the water contents are higher in the process. Further details on this damage mechanism can be seen from API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.6.

g) Naphthenic Acid Corrosion (NAC): (See API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.7 for details)

h) Phenol (Carbolic Acid) Corrosion: (See API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.8 for details)

i) Sulfuric Acid Corrosion: (See API‐RP‐571 Para 5.1.1.11 for details).